Fencing is a sport. Born in the days of blood combat, it is now a sport with rules, scoring methods, and special equipment.

The sport of fencing is fast and athletic, a far cry from the choreographed bouts you see on film or on the stage. Instead of swinging from a chandelier or leaping from balconies, you will see two fencers performing an intense dance on a 6-feet by 44-feet strip. The movement is so fast the touches are scored electrically—a lot more like Star Wars than Errol Flynn.

The Bout

Competitors win a fencing bout (what an individual “game” is called) by being the first to score 15 points (in direct elimination play) or 5 points (in preliminary pool play) against their opponent, or by having a higher score than their opponent when the time limit expires. Each time a fencer lands a valid hit—a touch—on their opponent, they receive one point. The time limit for direct elimination matches is nine minutes—three three-minute periods with a one-minute break between each.

Fencers are penalized for crossing the lateral boundaries of the strip, while retreating off the rear limit of their side results in a touch awarded to their opponent.

Team matches feature three fencers squaring off against another team of three in a “relay” format. Each team member fences every member of the opposing team in sequence over 9 rounds until one team reaches 45 touches or has the higher score when time expires in the final round.

Fencing at the Olympic Games will feature a single-elimination table format, much like that used in Tennis. There will be no preliminary rounds, as the initial seeding into the table will be determined by World Rankings.

The Weapons

Foil, epee, and saber are the three weapons used in the sport of fencing. While some fencers compete in all three events, elite generally choose to focus their energies on mastering one weapon.

Foil – The Sport of Kings

The foil is a descendant of the light court sword formerly used by nobility to train for duels. It has a flexible, rectangular blade approximately 35 inches in length and weighing less than one pound. Points are scored with the tip of the blade and must land on valid target: torso from shoulders to groin in the front and to the waist in the back. The arms, neck, head and legs are considered off-target – hits to this non-valid target temporarily halts the fencing action, but does not result any points being awarded. This concept of on-target and off-target evolved from the theory of 18th-century fencing masters, who instructed their pupils to only attack the vital areas of the body (i.e., the torso). Of course, the head is also a vital area of the body, but attacks to the face were considered unsporting and therefore discouraged.

Although top foil fencers still employ classical technique of parries and thrusts, the flexible nature of the foil blade permits the modern elite foil fencer to attack an opponent from seemingly impossible angles.

Competitors often “march” down the fencing strip at their opponent, looking to whip or flick the point of their blade at the flank or back of their opponent. Because parrying (blocking) these attacks can be very difficult, the modern game of foil has evolved into a complicated and exciting game of multiple feints, ducking and sudden, explosive attacks.

Rules: Understanding “Right-of-Way”

For newcomers to foil fencing, one of the challenging concepts to grasp is the rule of right-of-way. Right of Way is a theory of armed combat that determines who receives a point when the fencers have both landed hits during the same action. The most basic, and important, precept of right of way is that the fencer who started to attack first will receive the point if they hit valid target. Naturally, fencer who is being attacked must defend themselves with a parry, or somehow cause their opponent to miss in order to take over right of way and score a point. Furthermore, a fencer who hesitates for too long while advancing on their opponent gives up right-of-way to their opponent. A touch scored against an opponent who hesitated too long is called an attack in preparation or a stop-hit, depending on the circumstances.

Additionally, the referee may determine that the two fencers truly attacked each other simultaneously. This simultaneous attack is a kind of tie—no points are awarded, and the fencers are ordered back en garde by the referee to continue fencing

While it may be difficult to follow the referee’s calls (not helped by the fact that the officiating is performed in French!), the referee always clearly raises their hand on the side of the fencer for whom they have awarded a point. Watching for these hand signals can make it easier for newcomers to follow the momentum of a fencing bout without understanding all the intricacies of the rules.

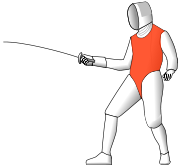

Equipment

Because foil actions often occur at blinding speed, an electrical scoring system was devised to detect hits on valid target. Each foil has a blunt, spring-loaded button at the point of the blade that must be depressed with a pressure of 500 grams or better to register a hit. The foil fencer’s uniform features an electrically wired metallic vest called a lamé—a hit to the lamé causes the scoring machine to display a colored light on the side of the fencer that scored the touch. Meanwhile, a hit off target—on the arms, legs or head, which are not covered by the lamés—causes the machine to display a white light. As mentioned earlier, hits off target stop the action of the match temporarily, but do not result in a touch being awarded. If the scoring machine displays both a colored light and a white light, it means the fencer quickly hit off target and then hit on target before the machine could lock out. In such situations, the fencer’s hit is ruled off target and no touch is awarded.

Another part of the fencer’s equipment is a special cable called a body cord. This plugs into his foil and runs though the sleeve of his arm out the back of his uniform, connecting to a retractable reel which is, in turn, connected to the scoring machine. Of course, with all this equipment a lot can go wrong, so before each foil bout commences, both fencers ceremoniously test each other’s lamés to ensure they are working properly.

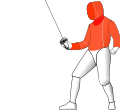

Epee – Freestyle Fencing

The epee (pronounced “EPP-pay”—literally meaning “sword” in French) is the descendant of the dueling sword, but is heavier, weighing approximately 27 ounces, with a stiffer, thicker blade and a larger guard. As in foil, touches are scored only with the point of the blade, however in epee the entire body, head-to-toe, is valid target—much like in an actual duel.

Similar to the foil, the point of the epee is fixed with a blunt, spring-loaded button. However, the epee tip requires more than 750 grams of pressure to register a touch with the scoring machine (basically, epee fencers have to hit harder). Because the entire body is a valid target area, epee fencers do not have to wear a metallic lamé. There is no concept of “off-target” in epee—anything goes.

Rules

Unlike foil, epee does not employ a system of “right-of-way.” Fencers score a point by hitting their opponent first. If the fencers hit each other within 1/25th of a second, both receive a point; this is commonly referred to as a double touch. The lack of right-of-way combined with a full-body target naturally makes epee a game of careful strategy and patience—wild, rash attacks are quickly punished with solid counter-attacks. So, rather than attacking outright, epeeists often spend several minutes probing their opponent’s defenses and maneuvering for distance before risking an attack. Others choose to stay on the defensive throughout the entire bout.

1996 was the first Olympics to feature team and individual Women’s Epee events.

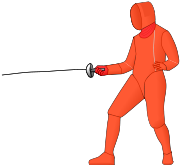

Saber – Hack and Slash

The saber is the modern version of the slashing cavalry sword. As such, the major difference between saber and the other two weapons is that saberists can score with the edge of their blade as well as their point. In saber, the target area is the entire body above the waist, excluding the hands. The lower half is not valid target, which is meant to simulate a cavalry rider on a horse. In addition, saber employs rules of right of way which are very similar to foil but with subtle differences. Like foil, the fencer who starts to attack first is given priority should his opponent counter-attack. However, saber referees are much less forgiving of hesitation by an attacker. It is common to see a saber fencer execute a stop cut against their opponent’s forearm during such a moment of hesitation, winning right of way an the point.

Again, as in foil, the saber fencer’s uniform features an electrically wired metallic lamé, which fully covers their valid target area. Because the head is valid target area, the fencer’s mask is also electrically wired. One significant departure from foil is that off-target hits do not register on the scoring machine, and therefore do not halt the fencing action. Saber fencing is also the first of the three weapons to feature a wireless scoring system.

If epee is the weapon of patient, defensive strategy, then saber is its polar opposite. In saber, the rules of right of way strongly favor the fencer who attacks first, and a mere graze by the blade against the lamé registers a touch with the scoring machine. These circumstances naturally make saber a fast, agressive game, with fencers rushing their opponent from the moment their referee gives the instruction to fence. In fact, a lopsided saber match can literally be over in seconds. As fending off the attack of a skilled opponent is nearly impossible, saber fencers very rarely purposely take the defensive. However, when forced to do so, they often go all-out using spectacular tactical combinations in which victory or defeat is determined by a hair’s breadth.

Athens was the first Olympics to feature a Women’s Saber event.

How to Watch a Fencing Bout

For those new to fencing, it can often be challenging to follow the lightning speed of the fencers’ actions. To become more comfortable in watching a fencing bout, it often helps focus on the actions of just one fencers. The fencer being attacked defends himself by use of a parry, a blocking-motion used to deflect the opponent’s blade, after which they may attempt to score with a riposte (literally “answer” in French). In fact, you may notice a particular cadence to the bout as the fencers rhythmically alternate roles as attacker and defender.

Fencers seek to maintain a safe distance from each other—that is, out of range of the other’s attack. Then, one may try to close this distance to gain the advantage for an attack. At times, a fencer will make a false attack—a feint—to probe the types of reactions and possible defenses by the opponent. Much of the fencing bout consists of this preparation, during which a fencer simultaneously determine their opponent’s true intentions while feeding them false information of their own. The complexity of this deadly “conversation” between the two opponents represents one of the more subtle beauties of the sport

Of course, eventually one or both fencers will land a valid hit. When this occurs, the referee stops the bout and, in foil and saber, determines who was the attacker, if their opponent successfully defended themselves, and which fencer should be awarded a touch, if any.